eth.limo - Everything you've wanted to know

A detailed overview of the journey and evolution of eth.limo's architecture

Introduction

Building eth.limo has been a rewarding and challenging experience. We serve (on average) 2.5 to 3 million requests per day across tens of thousands of ENS dWebsites with 99.999% monthly uptime. We originally launched eth.limo in August of 2021 and since then we have become a trusted partner within the ENS and Ethereum ecosystems. Our journey has not been without its struggles however. We are a tiny team of passionate and dedicated enthusiasts who wish to broaden the reach of the burgeoning decentralized web by not only showcasing its capabilities but also providing seamless access to content that is otherwise inaccessible without specialized clients and technical knowledge. The service is simple - append .limo to the end of any (properly configured) ENS domain name in the address bar and hit go, i.e. vitalik.eth.limo. We perform all of the on/off chain resolution and content retrieval behind the scenes and deliver it back to your browser.

The objective of this article is to outline the challenges and the journey of operating the eth.limo service. We’ll take a look at the challenges we’ve faced, the evolution of our architecture, the why and hows, and where we’ve landed to date.

The challenges

No good deed goes unpunished and we quickly began to realize that providing a performant and highly available public good is not without its own perils, both technical and non-technical:

Difficult to optimize for all content types - there are dozens if not hundreds of various frameworks and static site generators out there, being used in every imaginable capacity. In addition to static websites, there are JSON token lists, uncompressed and unoptimized images, etc, All of which need to be quickly delivered to the end user.

More than one way to skin a cat - Different encoding formats for IPFS CIDs, legacy formats, deprecated features, CCIP off-chain read, multiple storage protocols to name a few.

Subdomain support - ENS domains can support

Nsubdomains and developers often leverage these for versioning, communities, or just to segment dApps. Since wildcard x509 certificates only apply to one left label, we had to find a way of easily accommodating the issuance of thousands of certificates for an unknown number of hostnames.RPC calls - The true bottleneck of web3 adoption. Every on-chain read operation is a single RPC call (yes batching exists too), which normally wouldn’t be so bad if full execution clients were easy and cheap to run.

Cache TTLs and invalidation - How long should an ENS name be cached for? How should we invalidate stale content? Does this approach work for everyone? Ultimately we settled on a global 5m TTL for all resolved names.

IPFS - one of our favorite decentralized storage protocols. Operating a cluster of IPFS gateways isn’t trivial, but we collaborate closely with the Interplanetary Shipyard team which enables us to iron out any problems we may encounter. The Shipyard team is fantastic to work with, eth.limo could not easily operate in its current form without their hard work and dedication.

Abuse - as you can imagine, there are “bad actors” spinning up dWebsites with ENS for things like phishing, malware, animal abuse, etc. This poses quite the dilemma for “content moderation”, in terms of time and stress, especially when explaining to cloud providers that we don’t actually “host” the content.

Cost efficiency - Public goods by definition are non-excludable resources. This is great when a government can absorb the costs of maintenance and operations via MMT (modern monetary policy) but becomes something else altogether when operated privately.

Community support - we’re always happy to provide support and respond to feature requests from projects big to small, however we quickly learned that users also expect us to assist them with everything from IPNS troubleshooting, SEO optimization, referrals to complimentary services and so on. We had to ramp up quickly and create runbooks for commonly asked questions.

On-call support - As a small team, it’s imperative that we be able to quickly respond to, and triage production outages. Unfortunately, that means that we are on-call 24/7/365, which can add friction to our personal lives.

Too much to do, too little time - The web3 landscape shifts rapidly, leading to anxiety and stress, as well as an evergrowing backlog of “nice to haves”. Juggling this is not only a challenge from a managerial standpoint, but also a psychological one.

Funding - We never know where our next meal will come from. We don’t charge for the service (it’s a public good afterall), so finding reliable revenue streams is a top priority. Thankfully we have been blessed with grant funding from a number of sources, including the Ethereum Foundation, ENS DAO, Optimism RPGF, Gitcoin, Giveth, and others.

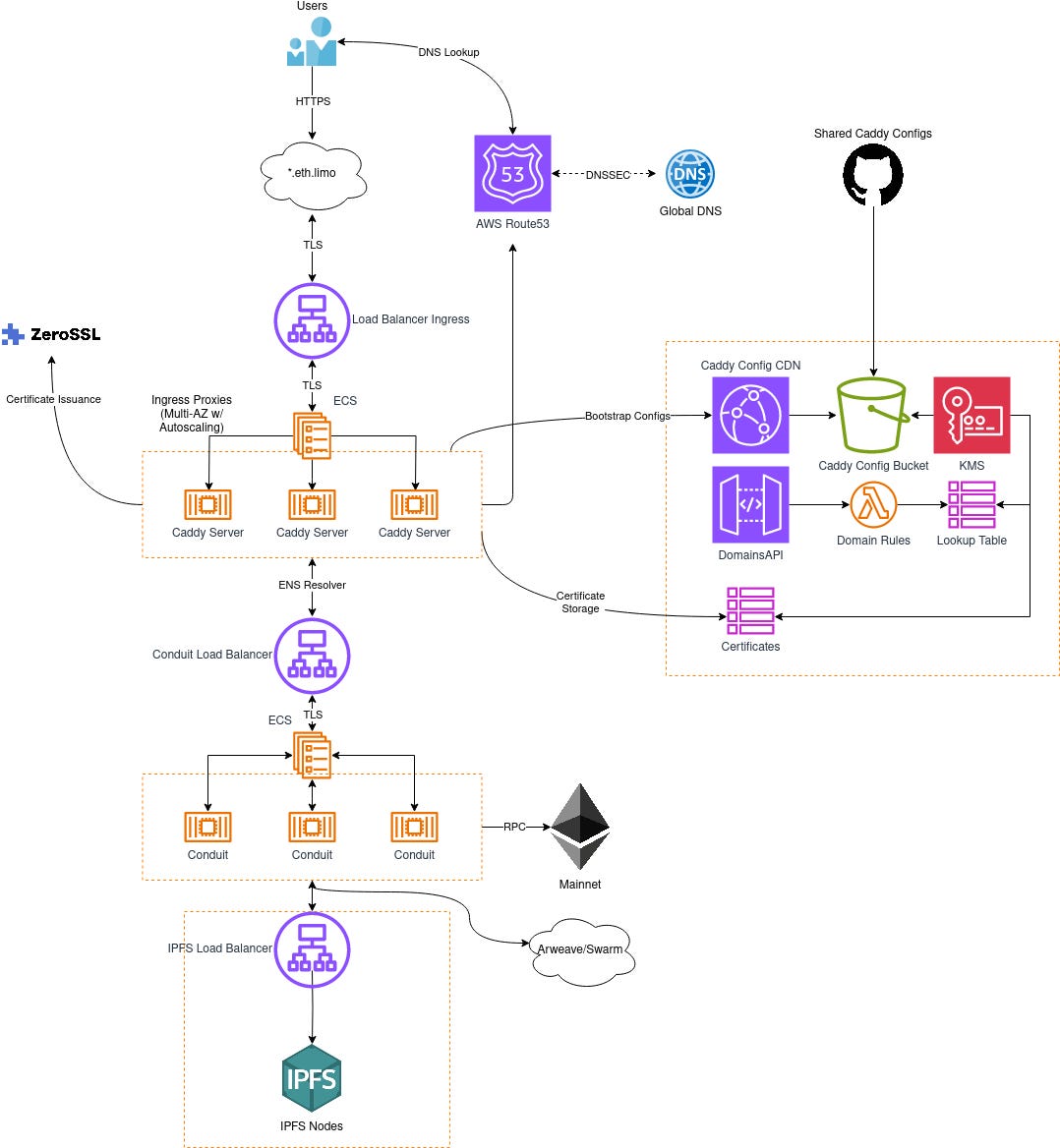

Conceptual overview

At a high level, eth.limo is essentially a fancy reverse proxy:

The service is responsible for performing the following operations:

Terminate TLS connections for a given hostname, in this case vitalik.eth.limo.

Perform RPC calls to the ENS registry and resolver contracts in order to fetch the records of vitalik.eth. Currently we only support the Ethereum Mainnet for registrar queries, however we do support CCIP-read for other resolver data.

Decode the contentHash record.

Determine which storage protocol is used, in this case it would be IPFS.

Proxy the request to the appropriate storage gateway and return the content back to the client.

The stack

While many things have changed along the way, Caddy server has been an invaluable component of the eth.limo application stack. We cannot praise it enough - from its fantastic ACME client, easy to use configuration, and blazingly fast performance, Caddy is the backbone of our architecture.

In addition to Caddy, we use the following:

Kubo (IPFS client/gateway)

ethers.js (main resolver API)

Redis (caching layer for the API)

Various cloud services - container schedulers, CDNs, etc.

Version 1.0

The OG eth.limo stack was originally created as a single deployable Helm chart. The initial configuration consisted of Caddy server for the ingress, which then forwarded requests to Kubo (IPFS client). Kubo was configured to use DNS over HTTPS for resolving .eth domains, which forwarded requests to CoreDNS using the go-ens module. This worked well, however it was not necessarily cost efficient and we ran into the following issues:

Cumbersome management. Required ArgoCD (great tool), but it was a little overkill for our use case.

Helm templates weren’t very readable, especially for new users

Since we were using Kubo and CoreDNS, we had no ability to support different storage protocols, only IPFS.

At the time, go-ens had no CCIP support, so all reads were limited to mainnet.

Difficult to manage caddy JSON config (some modules weren’t supported in Caddyfile syntax).

Not easy to run in a multi-cloud environment without duplicating the entire stack.

Caching was limited to CoreDNS.

No unicode (emoji) support for ENS names.

Version 2

With the growing popularity of CCIP-read (ERC-3668), we realized that we needed to add support for that feature sooner rather than later. Additionally we wanted to be able to support N subdomains using Caddy’s on-demand TLS features. Unfortunately (at the time), the go-ens library was unmaintained, so continuing to use CoreDNS was out of the question. Instead we opted to write our own proxy implementation using ethers.js and a NodeJS backend. Controlling our own proxy codebase enabled us to support the following features:

Intelligent content routing (Arweave/Swarm/Skynet/IPFS & IPNS).

CCIP-read and Unicode domain support.

IPFS CIDv1 formats.

DNS over HTTPS endpoint.

Custom /ask endpoint for Caddy server to use when determining if a subdomain was valid for certificate issuance.

Resolver caching - Instead of making an RPC call for each HTTP request, we decided to sacrifice immediate consistency in favor of better performance with Redis in-memory caching.

This time we opted to ditch Kubernetes in favor of “serverless” runtimes. We wanted to reduce operational overhead on our team, leverage security guarantees provided by the Shared Responsibility Model, turn on DNSSEC, and take advantage of no hassle autoscaling. This configuration worked well for us, however we neglected to use RPC failover connections and we were limited to a single certificate authority (ZeroSSL) due to the non-existent ratelimits for paid accounts. At the time we were unsuccessful in applying for Let’s Encrypt rate limit exemptions (more on that later).

We also ran into a few other “problems” with the v2 architecture:

Duplicated data transfer with redundant proxies (more expensive and slower) since we were handling traffic synchronously: Request → Caddy → Conduit → Storage backend.

Caddy still relied upon the JSON format for configuration due to the lift-n-shift approach, which resulted in some really ugly Go templates with JSON.

We ended up running variations of the v2 architecture for a little over a year and a half. The codebase was easy enough to manage, the infrastructure was mostly self-healing, but we knew we could do better.

Version 3

Enter the first phase of our new v3 architecture. We took into consideration all of the lessons learned from our previous iterations and decided to double down on what worked and refactor what didn’t. One of the biggest improvements we made was to completely decouple HTTP proxy logic and data transfer from the ENS resolver API. The new request flow looks like this:

User Request → Caddy → Proxy API

Proxy API --${Location}→ Caddy → Storage Backend

Storage backend → Caddy → Response to User

Summarized by this Caddyfile (localhost example):

{

admin off

auto_https off

local_certs

log {

level INFO

format console

}

}

&(dweb-api) {

reverse_proxy localhost:8888 {

transport http

method GET

header_up Host (.*[-a-z0-9]+\.eth) $1

@proxy status 200

handle_response @proxy {

@trailing vars_regexp trailing {rp.header.X-Content-Path} ^(.*)/$

reverse_proxy @trailing {rp.header.X-Content-Location} {

rewrite {re.trailing.1}{uri}

header_up Host {rp.header.X-Content-Location}

transport http {

dial_timeout 2s

}

@redirect301 status 301

handle_response @redirect301 {

redir {rp.header.Location} permanent

}

}

}

}

}

:8443 {

log {

level INFO

format console

}

bind 0.0.0.0

tls internal {

on_demand

}

invoke dweb-api

}

As part of this new architecture migration we also wanted to sow some multi-cloud seeds so that from a disaster recovery standpoint, we would be able to continue serving traffic in the event of a catastrophe, easily decouple the Caddy ingress proxies from the rest of the stack for preparing to deploy multi-region ingresses across any cloud or VPS host, and take advantage of cost deltas for bandwidth intensive processes like IPFS. Additionally GCP’s Cloud Run service offers a “scale to 0” feature which is quite nice for development and testing environments. Unfortunately Cloud Run does not support TCP based load balancing, which is a requirement for our Caddy ingress to work with subdomain certificates, so we continued to use AWS Fargate for our serverless container scheduler and runtime. GCP cloud load balancing and CDN services also offer anycast addressing out of the box, which is great for designing multi-region traffic routing.

We were also able to successfully raise the Let’s Encrypt rate limits for the eth.limo domain, allowing us to primarily issue certificates from them and failover to ZeroSSL in the event of a problem. This has the added bonus of allowing us to begin the process of adding the eth.limo domain to the Public Suffix List.

Let’s review some of the other new features included in v3:

Multiple RPC providers for lookup failover. In addition to Alchemy, we also have begun using dRPC.

Arweave name service (ARNS) resolution.

Full end to end IPv6.

IPFS malicious content list integration.

Easily reproducible for local environments (dApp Node, etc)

IPFS CDN with _rewrites file support. Static content is now cached and much faster on retrieval.

Easy Caddyfile configuration with dynamic configuration reloads.

Custom domain routing logic (now possible to map CNAMEs for ENS internally. Note this feature is still a WIP).

At eth.limo, we view our v3 architecture as a necessary step in ironing out old pain points, setting the stage for multiple regions, and facilitating local and user controlled ENS gateways.